Rewilding the Mekong – Strategies for saving a river on the brink of collapse

The Mekong’s sustainability gamble

For the water-rich countries of the Mekong River Basin, hydropower has been long been a key strategy for economic development. However, these economic benefits come at significant environmental cost, with 124 large dams operating or planned in the Lower Mekong Basin and 18 more on the Upper Mekong (Lancang River), the ecological integrity of the entire system is under severe threat as the network of reservoirs fragment connectivity in the fluvial system disrupting natural processes of water, sediment, nutrient and fish transportation.

One of the most alarming consequences has been the dramatic reduction in sediment transport. The Mekong's natural sediment load of approximately 160 million tons per year has already declined by 70% to just 49 million tons annually. If all planned hydropower projects are completed, this could further drop to a mere 9.3 million tons—a catastrophic 95% reduction from natural levels.

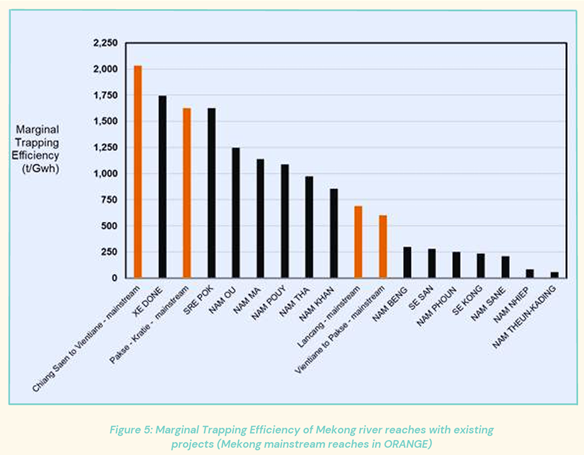

On the other side of the trade off, in 2022, the basin's dams produced 146,585 GWh of electricity while preventing 110 million tons of sediment from flowing downstream each year. This amounts to approximately 750 tons of sediment lost annually for each GWh of electricity produced from hydropower, with much higher trapping efficiencies for Mekong mainstream reaches, the Xe Done, Sre Pok and Nam Ou Rivers.

This sediment starvation has far-reaching consequences that are now pervasive in Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam: riverbank erosion, reduced floodplain fertility, a shrinking and sinking delta, increased saline intrusion, wetland degradation, fisheries collapse, food insecurity, and growing economic inequality in rural areas. All of these issues have escalated across the lower Mekong basin in the past decade due to the combined influence of river fragmentation and climate change.

Collapse of National Highway No. 91 in An Giang Province, Vietnam, May 27, 2020 Image Source Tui Tre News, 2020

“Given the importance of sediments to nutrient transport, erosion and deposition processes, delta stability, and fisheries and agricultural productivity, this decline is alarming. The loss of sediments in the river is only likely to increase with further construction of dams and sand mining. One worst case scenario suggests the sediment load by the time the flow reaches Kratie could almost disappear by 2040” (Mekong Basin Development Strategy, MRC 2021).

Since 2021, the Mekong River Commission (MRC) has acknowledged this crisis in its Basin Development Strategy but treats it as an inevitable trade-off for economic development. Significant economic growth at substantial environmental cost.

For many governments and development partners the focus has shifted. Accept the collapse in Mekong sediments as a fait accompli and ramp up efforts to address the adverse impacts of reduced sediment transport by addressing river and coastal erosion, subsidence and floodplain fertility at the local scale.

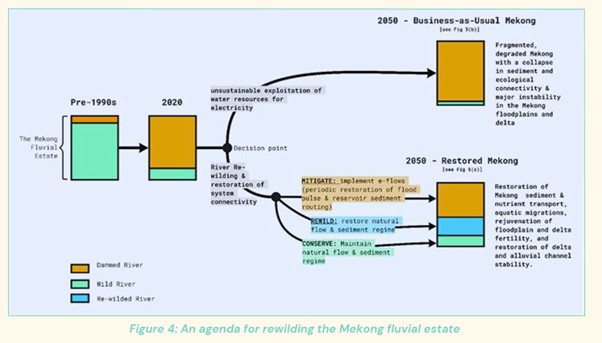

A New Path Forward: Rewilding the Mekong

In 2022, working with Chulalongkorn University, AMPERES convened 26 researchers from Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, Australia, China, Hong Kong, and the USA to explore alternative futures for the Mekong’s electricity transition. In this book, we question the inevitability of current development trajectories – including the trade-off between hydropower and environmental decline.

We explored "rewilding" as a transformative strategy to restore the Mekong's ecological functions while maintaining energy security. River rewilding aims to restore connectivity between ecosystems by removing human-made barriers, focusing particularly on restoring natural flow and sediment regimes.

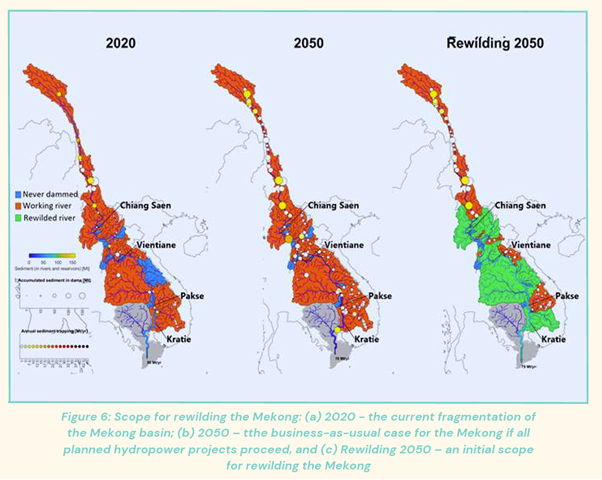

For the Mekong we assessed the geospatial distribution of dams against the sediment provenance and transport dynamics for all tributaries, classifying the catchments into free-flowing, their level of fragmentation. Working with Stanford University and University of California Berkeley we modelled of thousands of possible permutations of dam portfolio development in the Mekong and identified specific river reaches where dam removal would yield the greatest ecological benefits relative to energy production losses, using a metric called "Marginal Trapping Efficiency" (MTE). We then interpreted the global approach to rewilding to identify three main strategic objectives for the three main zones identified:

- Preservation of free-flowing tributaries: Only 9% of the Mekong's tributary catchments remain free-flowing, and this could decrease to just 3% by 2050. Protecting these remnant wild rivers through "Intact Rivers" policies is essential.

- Removal of low efficiency (MTE) dams : Removing dams from key tributaries where ecological benefits outweigh energy production benefits would restore sediment flow.

- Improved sediment management for high MTE dams: For dams that remain, implementing environmental flow regimes and coordinated sediment passage through the intermittent restoration of the flood pulse could partially mitigate impacts.

Strategic Priorities for Rewilding

Our work indicates that a strategic rewilding program could restore sediment load at Kratie to 87 million tons per year— 54% of the pre-dam level. This would require:

- Removal of all Lower Mekong mainstream dams

- Removal of large dams in seven key tributaries: Xe Done, Nam Ou, Nam Tha, Nam Ma, Nam Khan, Nam Pouy, and Sre Pok

This approach would reconnect 90% of the fragmented Lower Mekong sediment load to the downstream floodplain, while foregoing approximately 26,854 GWh of annual electricity generation. Together with an intact rivers policy for the 9% of remnant free-flowing tributaries, this could reconnect the floodplains of Cambodia and the Mekong delta with a vital annual supply of sediment.

Addressing Implementation Challenges

Removing dams is a controversial recommendation, but we argue, one that must be asked. We acknowledge significant political and economic barriers to dam removal, including:

- Loss of power generation: The 26,854 GWh of annual electricity that would be lost must be replaced. Fortunately, rapidly advancing non-hydro renewables (solar, wind) offer increasingly cost-effective alternatives, and there is growing understanding of the complementarity between these renewables and hydropower (e.g. floating PV on hydropower reservoirs).

- Financial compensation: Investors who would face losses from early dam decommissioning would require compensation. Our paper suggests adapting models similar to those being developed for early coal plant retirement in Southeast Asia, using blended finance approaches.

- Political resistance: Dam development has created powerful vested interests, both formal and informal. Any rewilding strategy must address these political economy dynamics by potentially preserving rent-seeking opportunities through alternative infrastructure investments.

- Investment confidence: To prevent damage to the investment climate, compensation mechanisms must be clearly established.

Policy Recommendations

- Develop an "Intact Rivers" policy for the Mekong Basin to protect the remaining free-flowing tributaries from future development.

- Create a basin-wide sediment management plan that prioritizes the restoration of sediment connectivity through strategic dam removal.

- Establish compensation mechanisms for affected investors, potentially modeled after early coal plant retirement schemes.

- Accelerate investment in non-hydro renewables (solar, wind, and floating solar on remaining reservoirs) to replace foregone hydropower generation.

- Improve environmental and social due diligence for any future water infrastructure projects to avoid repeating past mistakes.

- Develop a binding, integrated river basin plan that gives equal weight to environmental protection, social resilience, and economic development.

Conclusion

The current development trajectory of the Mekong Basin is unsustainable and cannot be accepted as a fait accompli. Rewilding offers a viable alternative that recalibrates the trade-off between energy and the environment. While ambitious, the rewilding approach recognizes that decisions once considered irreversible can be changed as new information emerges and alternative technologies develop.

The emergence of cost-competitive renewable energy sources creates a unique opportunity to recalibrate the trade-off between energy production and ecological health. By strategically removing dams from the most ecologically sensitive areas while developing alternative energy sources, Mekong countries can restore much of the river's ecological function while maintaining energy security.

This rewilding agenda would represent a profound shift in the region's development approach, requiring substantial political will and international cooperation. However, the alternative—continuing on the current path of ecological degradation—threatens the livelihoods of millions and the long-term sustainability of the entire Mekong Basin.